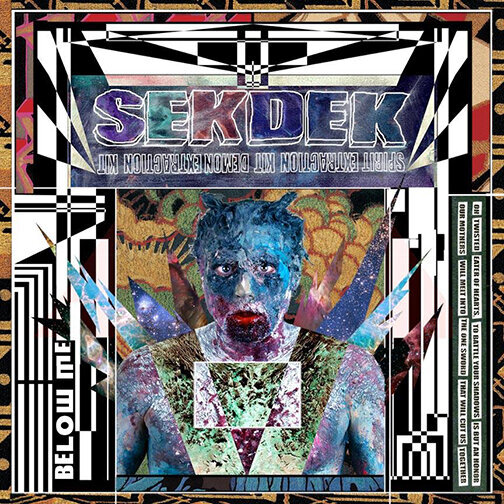

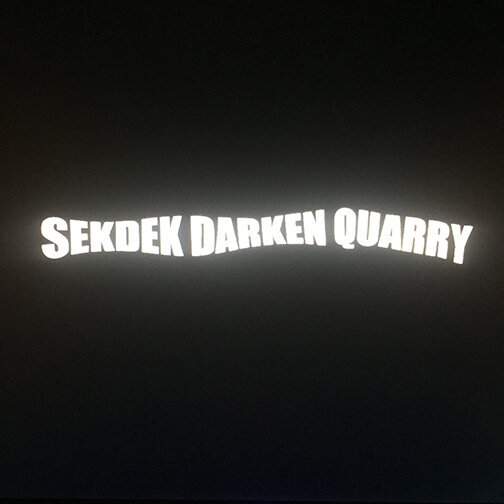

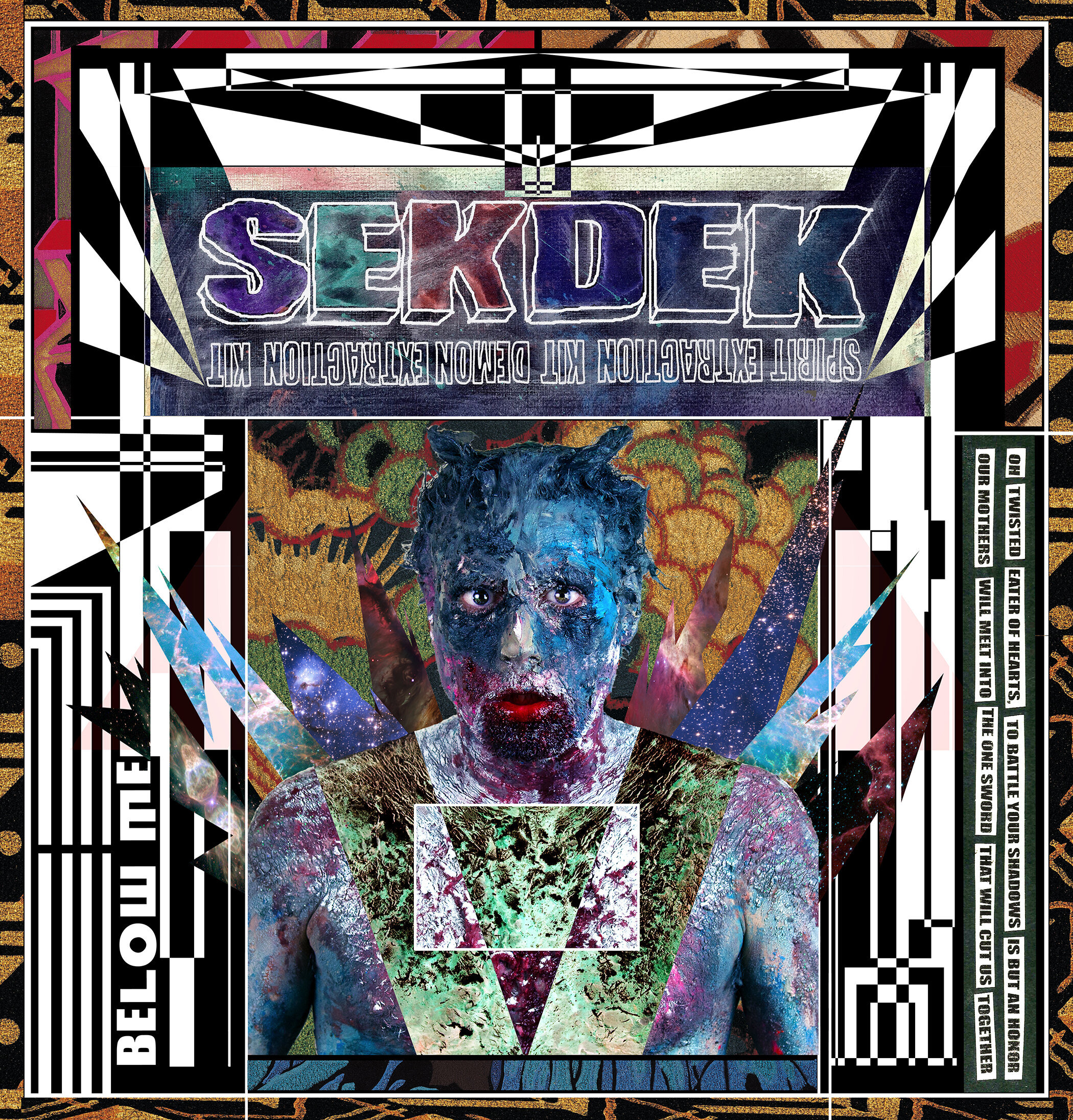

Necessary Distance from the Witch

Sekdek is not a flirtation with the demonic, nor is it a modern dalliance with evil or an alliance with some Illuminati-like cabal accused of saturating pop music with cultic paganism, witchy theatrics, and eerie spell-casting occultism. It also distances itself from the troubling, tribally sanctioned mass hypnotic rituals or overly sexualized manipulations that have become disturbingly common in the modern pop, thrusting, gyrating, pole-dancing context of Super Bowl media.

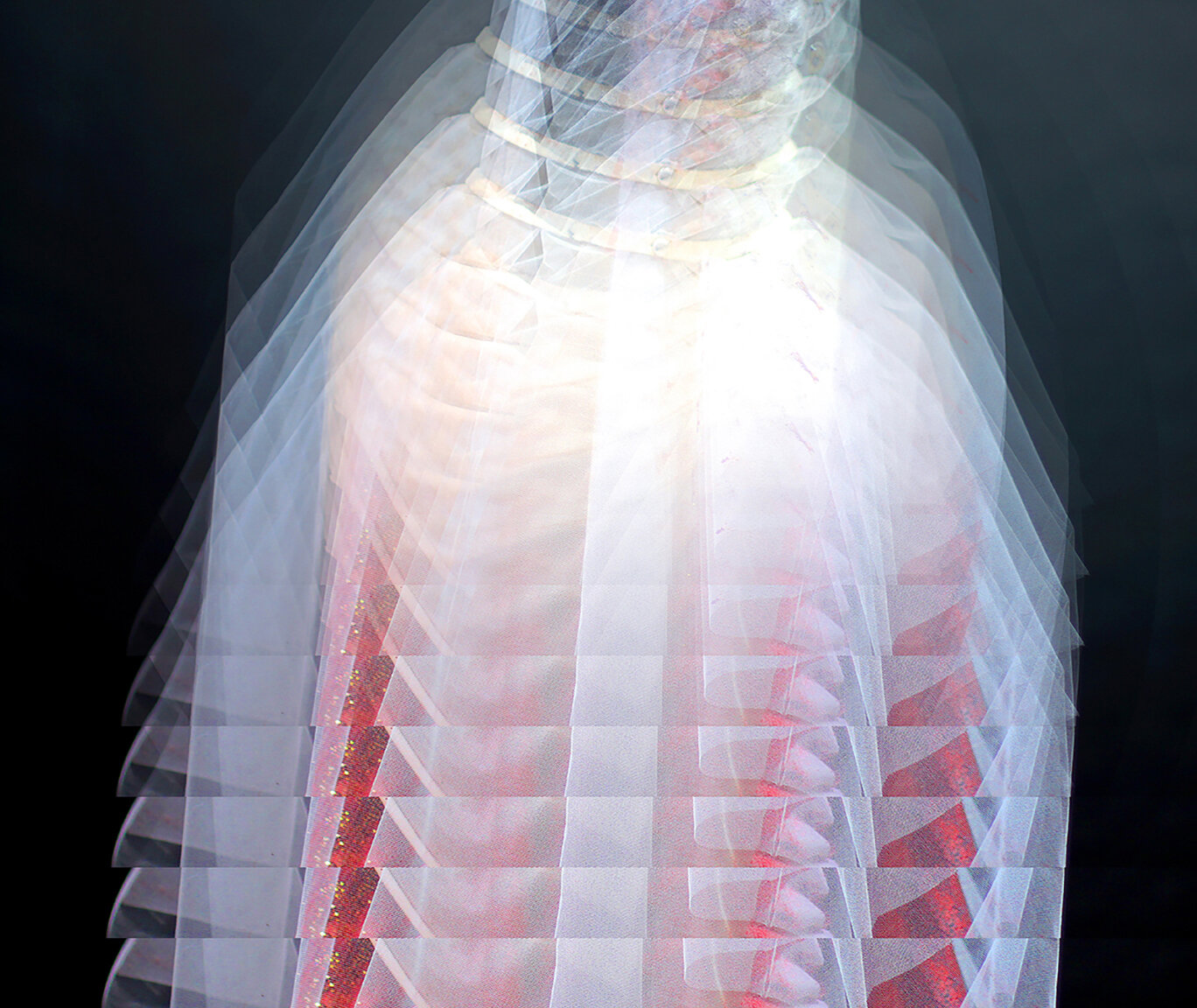

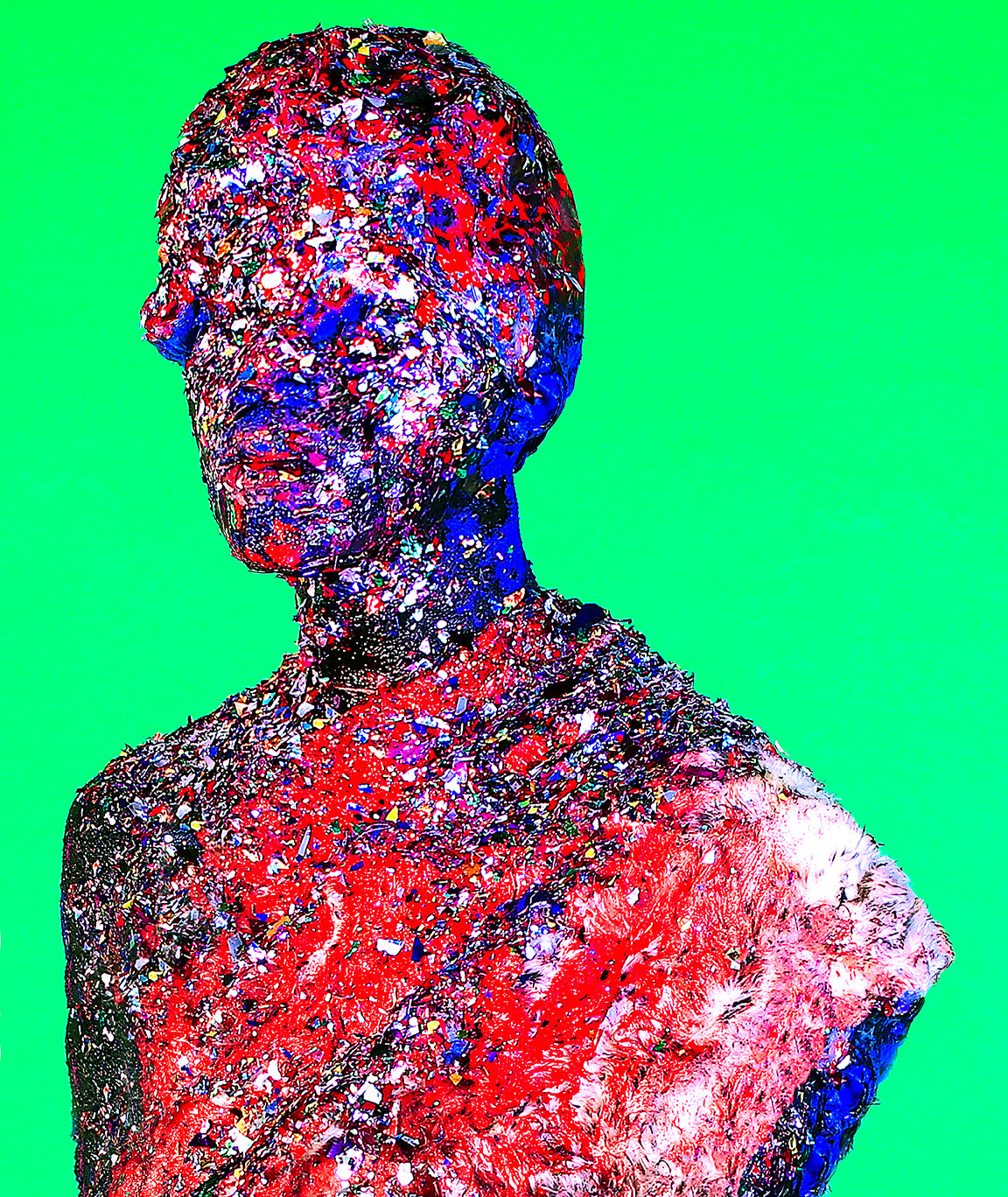

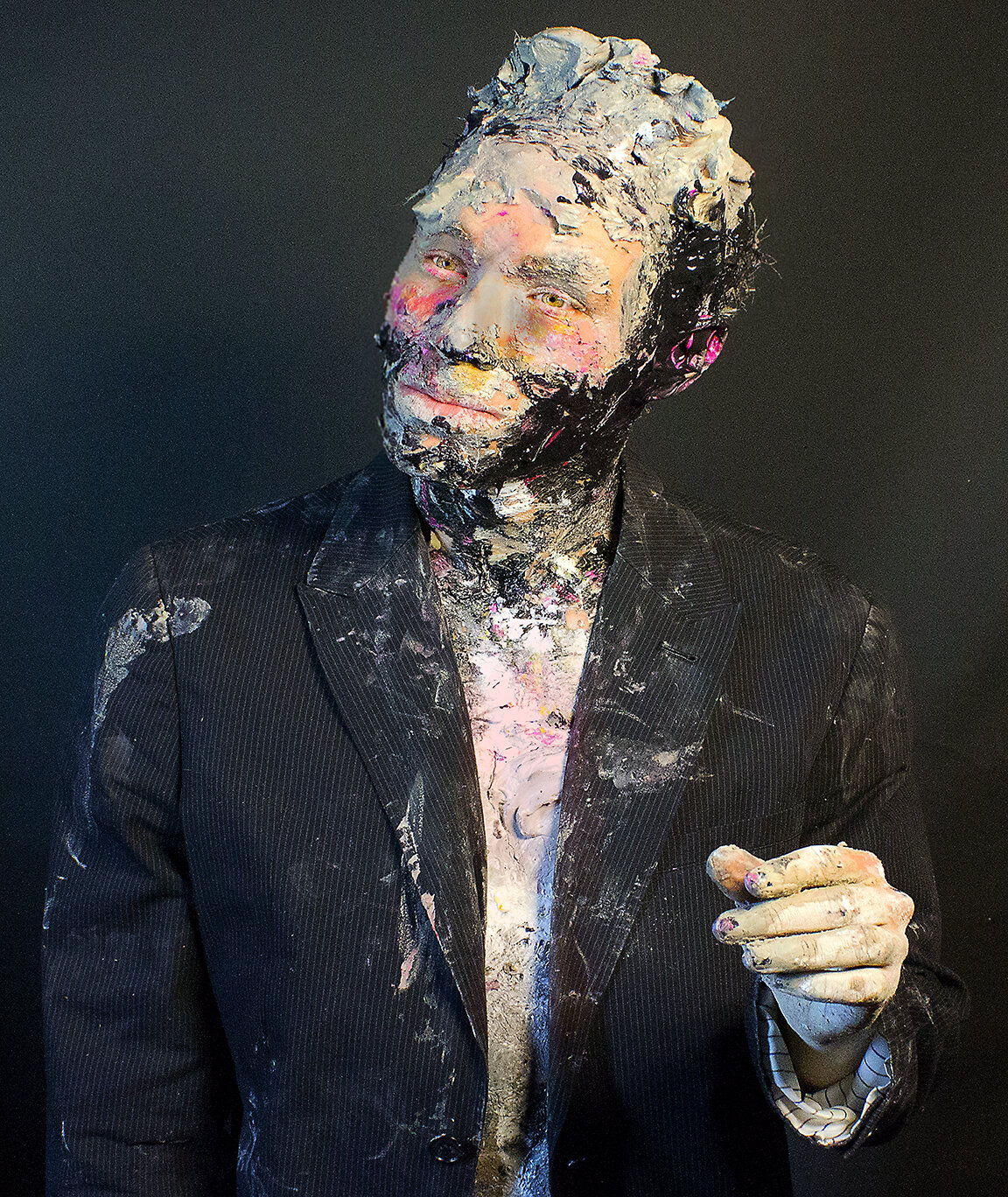

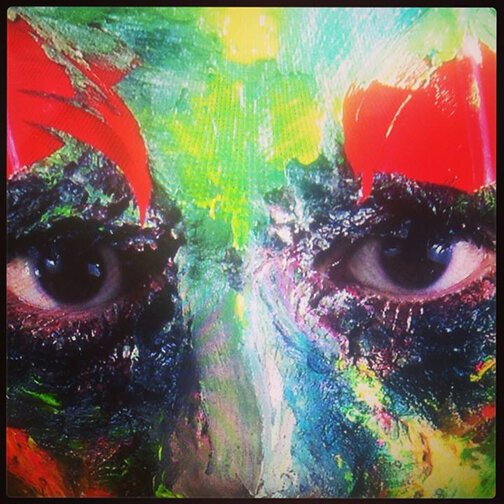

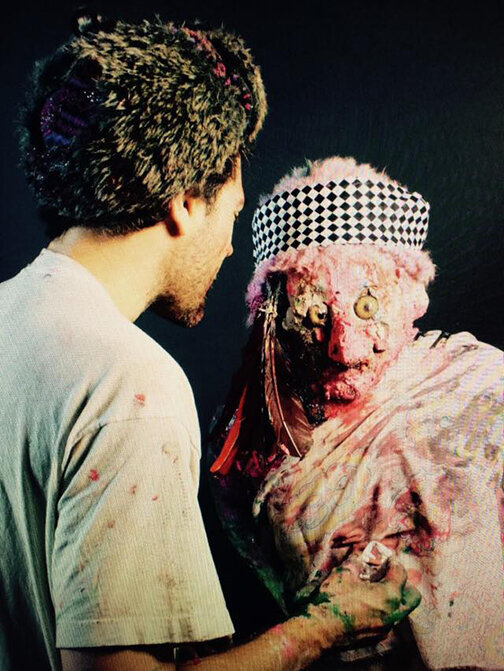

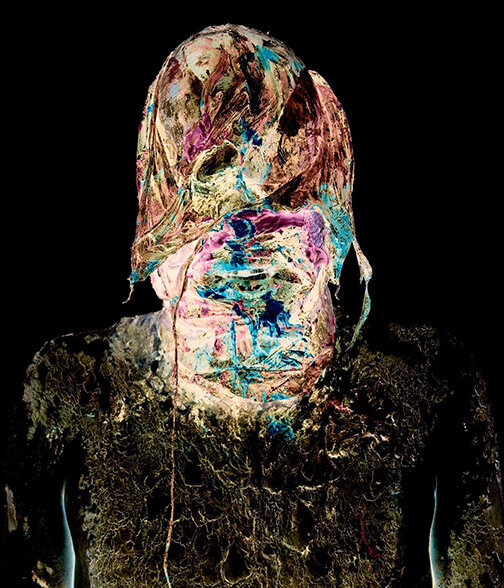

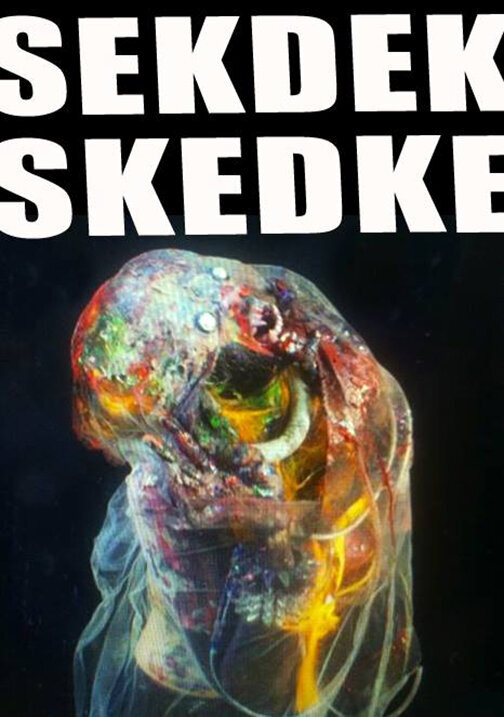

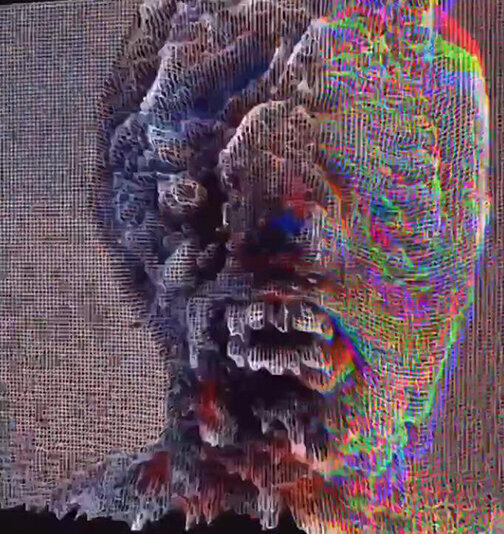

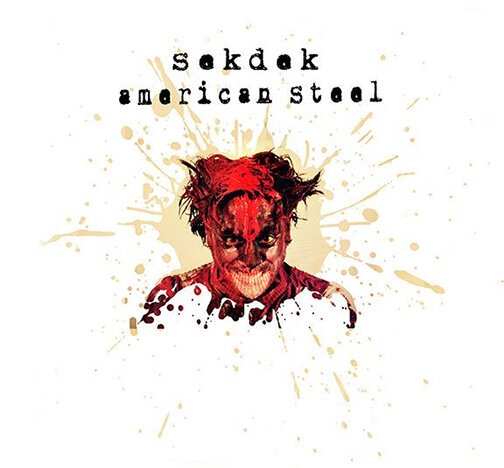

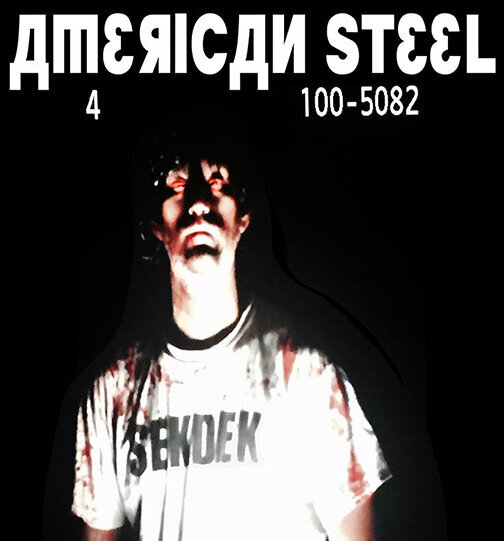

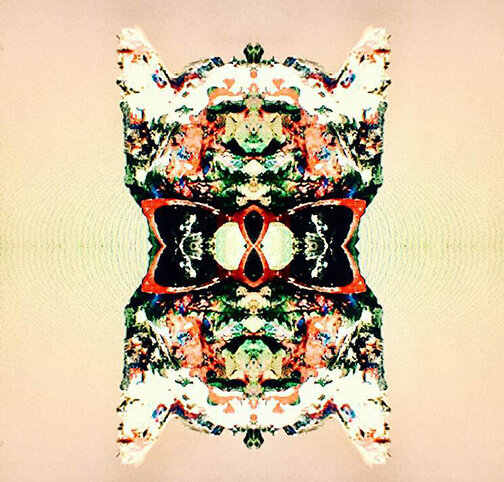

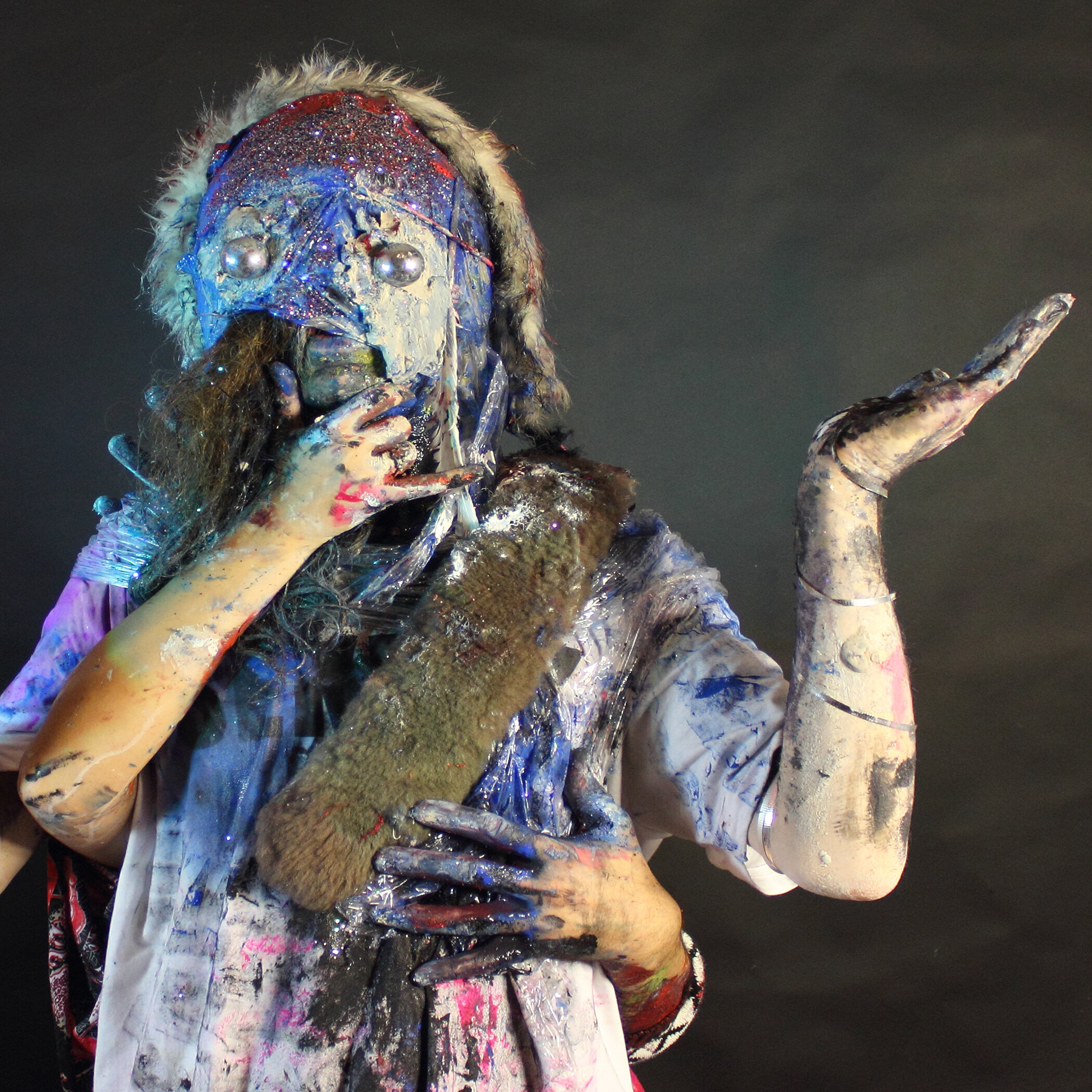

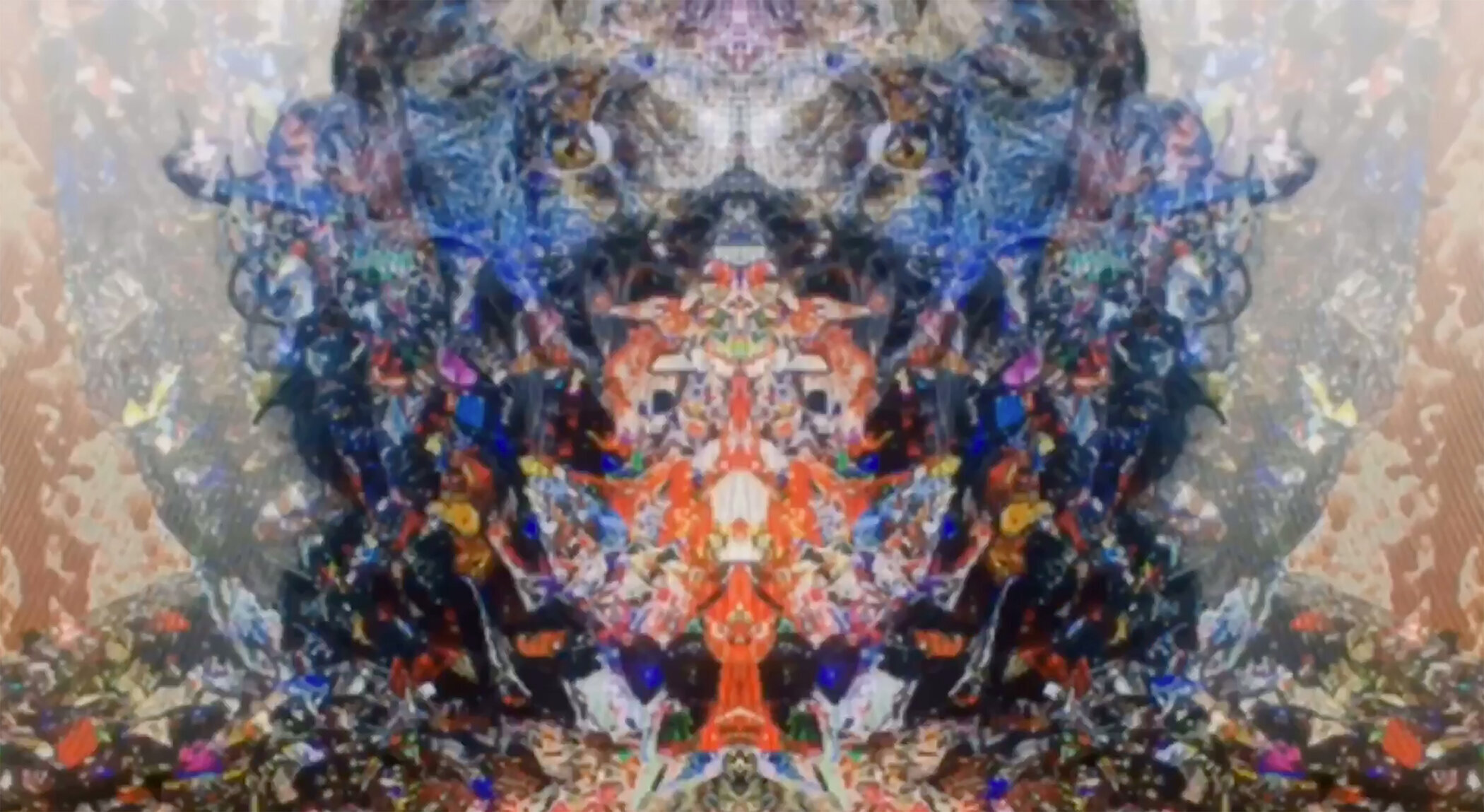

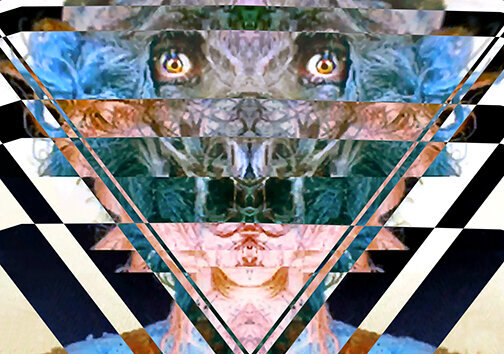

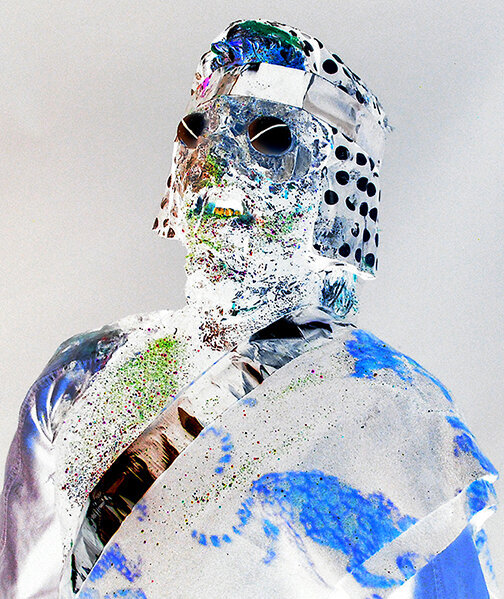

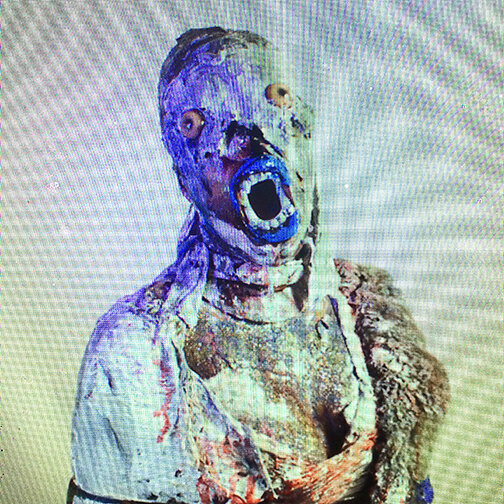

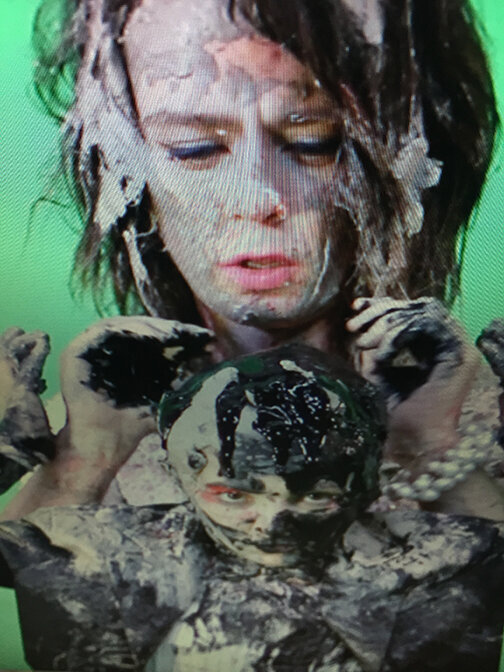

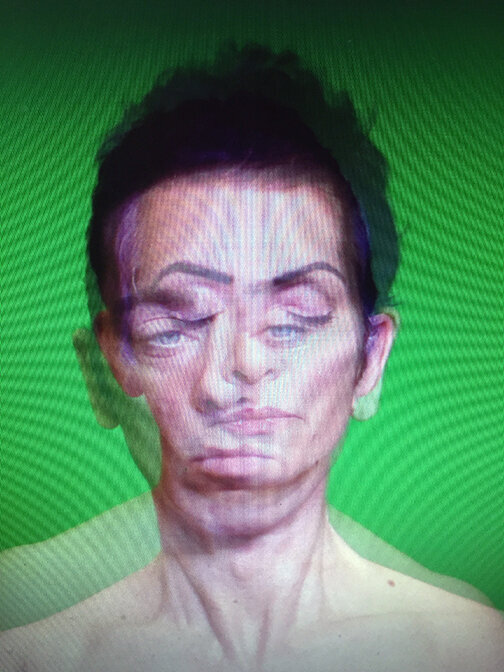

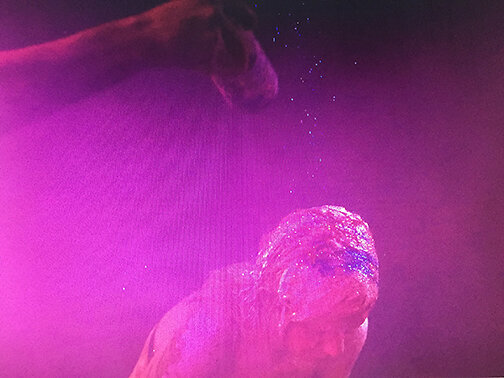

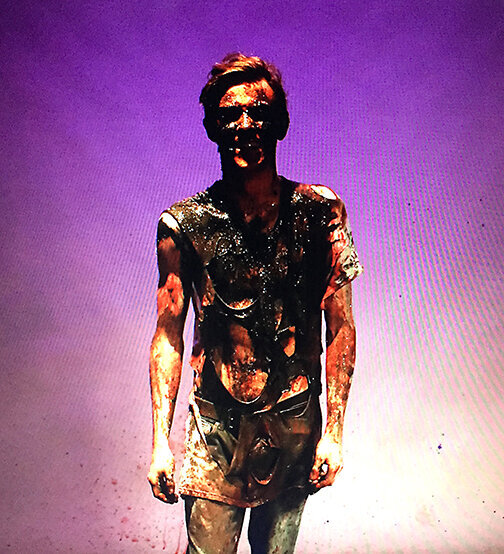

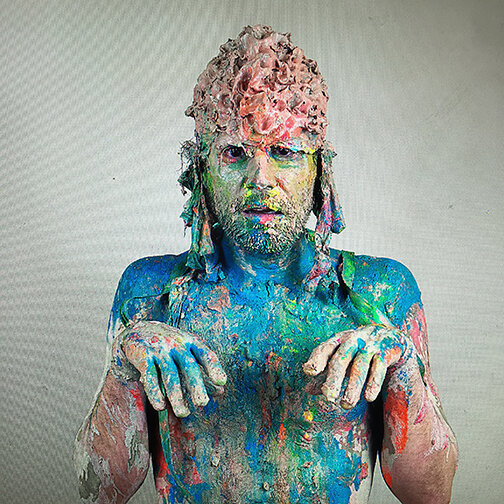

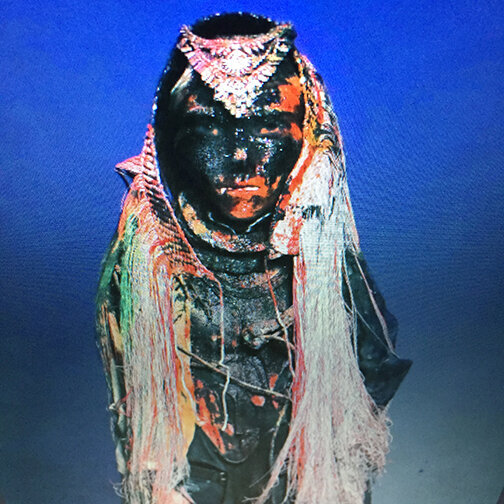

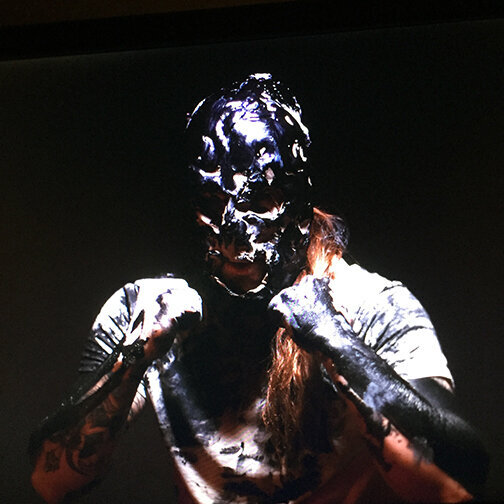

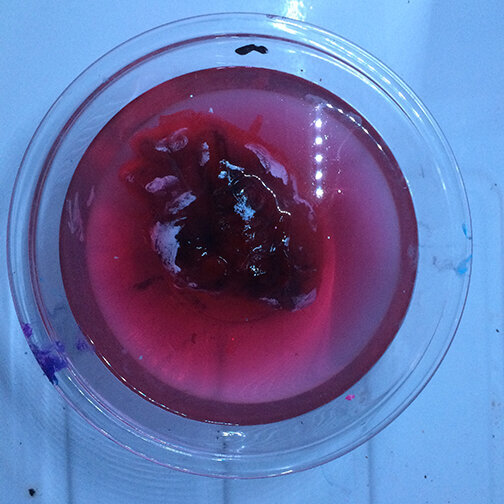

The bonus goal here, beyond inspiring giggles, wtfs, and legitimate awe, is to craft an artful spiritual exorcism—a deliberate extraction of the stigmata of evil embedded in imagery, transforming it into something uniquely powerful and profoundly beautiful. The nuance of these works is essential: many figures hint at humor, goodness, and a kind of benevolent power in their expressions and poses. While the imagery may initially evoke mythical archetypes such as Baphomet, Shiva, Medusa, Quetzalcoatl, or even Vlad the Impaler, these representations undergo a metamorphic alchemy. They emerge not as symbols of terror but as friendly, enlightened beings, their darkness transmuted into radiant light through the creative process. This is art as redemption—a studio spotlight cast upon humanity's shadow, daring us to confront our dualities through bold, often shocking aesthetics. It's about making friends with our shadows—giving Grendel a loving pat on the back and whispering, "It's okay. I love you." The goal is never to traumatize or shock for its own sake but to provoke a deeper examination of good, evil, and the stigmas entrenched in visual culture.

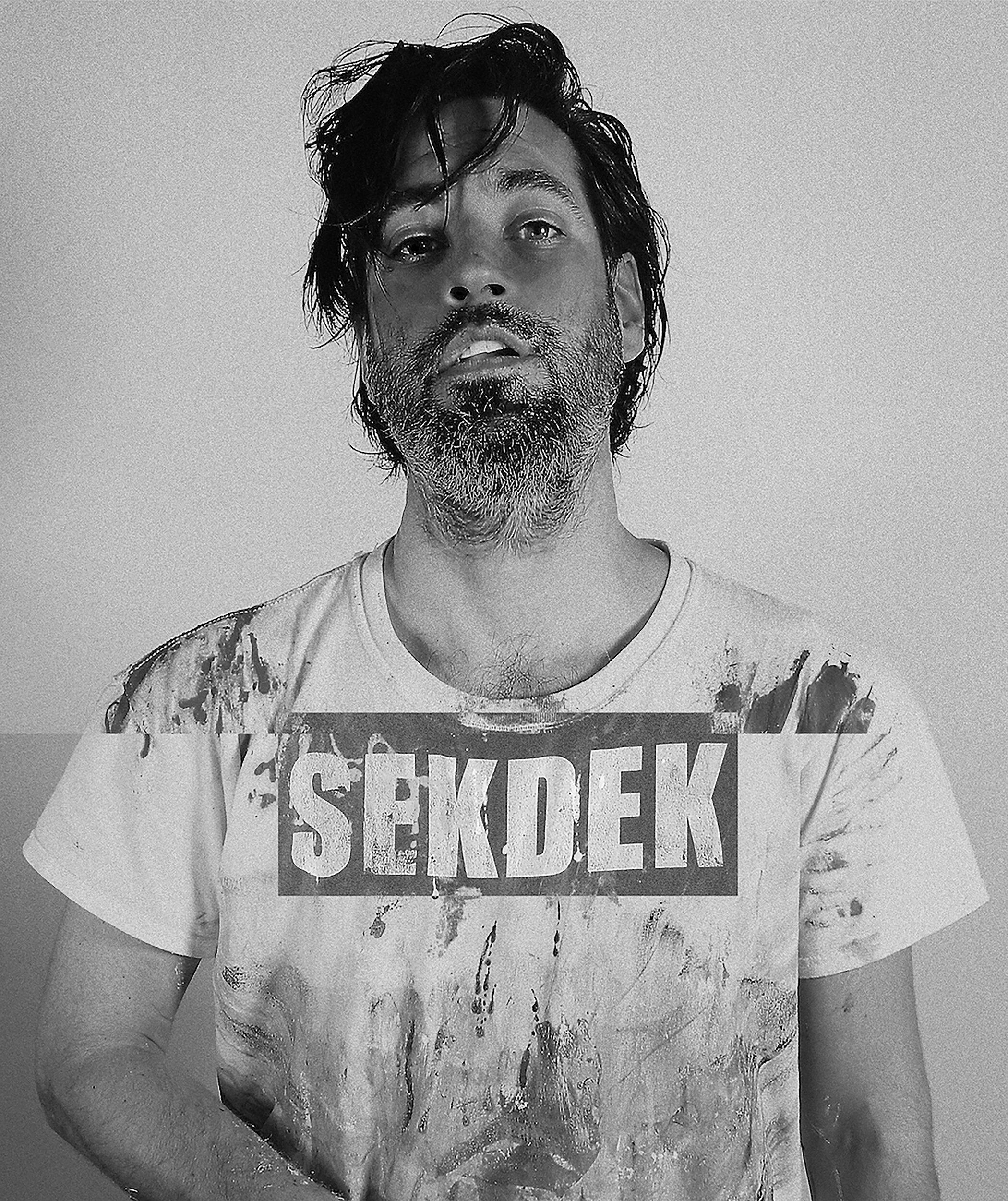

Most are quick to judge anything that strays from sanitize new aged swaddled mandala innocence, Sekdek insists on representing metaversional reality in its full-bodied complexity—mythological, human, and spiritual. Through these images, we (multiple Is) seek to nudge the scales of evil toward good, employing telepathic and counter hypnotistic methodology to Wesley Willis viewers into seeing a crack in the code—a fleeting moment when what was once feared or reviled transforms into something lovable and relatable. It is an act of reconciliation, popping devils into angels, the grotesque into the divine, and fear into friendship. This creative process challenges us to confront and embrace our own shadow, not with fear, but with a transformative love that redeems the darkest corners of the imagination.

Spoken by Louis Denardo, Jacob's friend and chiropractor, played by Danny Aiello in the 1990 film Jacob's Ladder. Louis shares this wisdom with Jacob Singer, the protagonist portrayed by Tim Robbins, during a pivotal moment in the movie. "The only thing that burns in Hell is the part of you that won't let go of life—your memories, your attachments. They burn them all away. But they're not punishing you," he said. "They're freeing your soul. If you're frightened of dying and you're holding on, you'll see devils tearing your life away. But if you've made your peace, then the devils are really angels, freeing you from the earth." This moment encapsulates one of the film's central themes: the transformative journey of facing inner demons and finding peace with one's past, fears, and mortality. Danny Aiello's calm yet profound delivery makes this scene unforgettable and emotionally resonant.

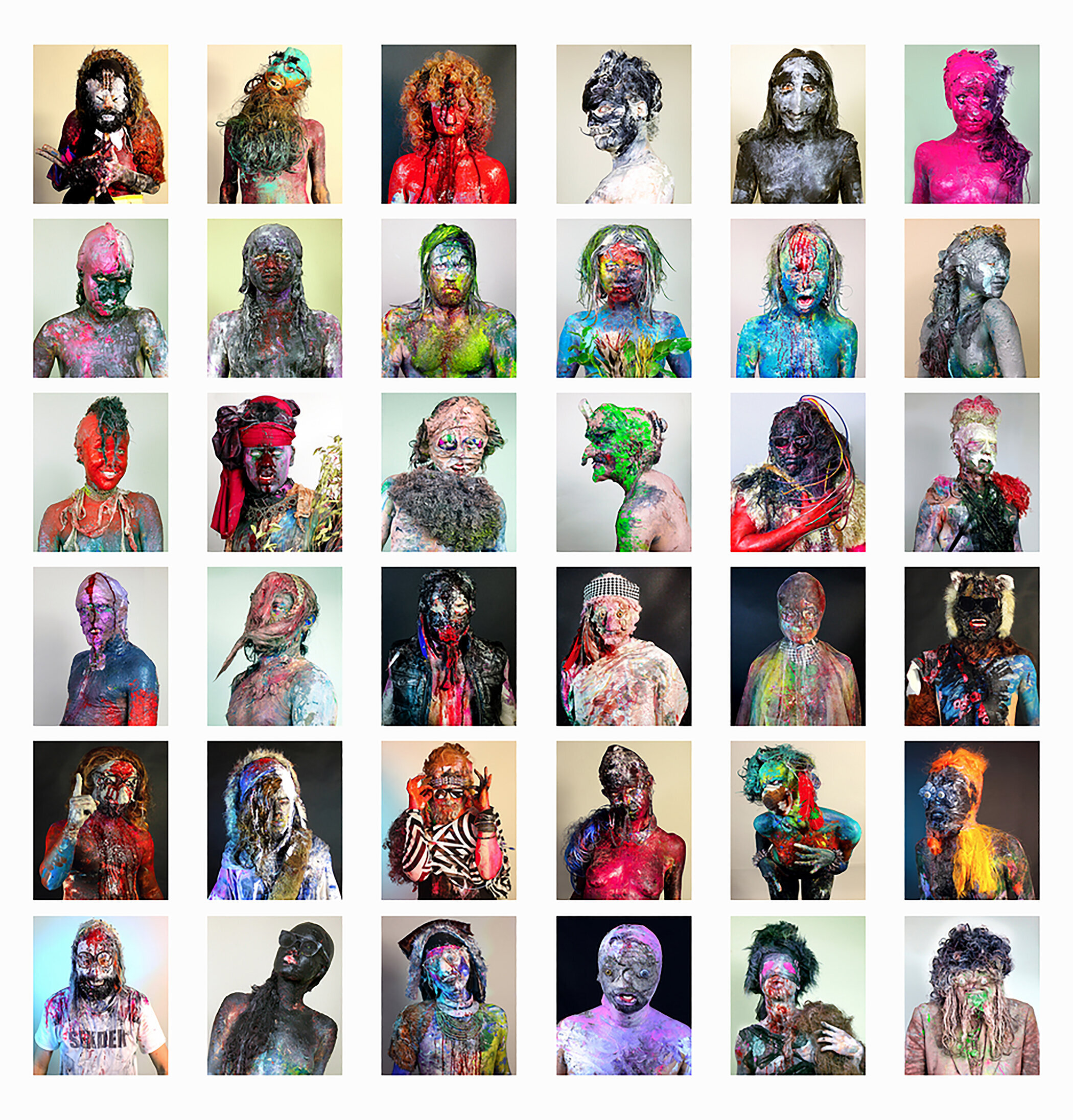

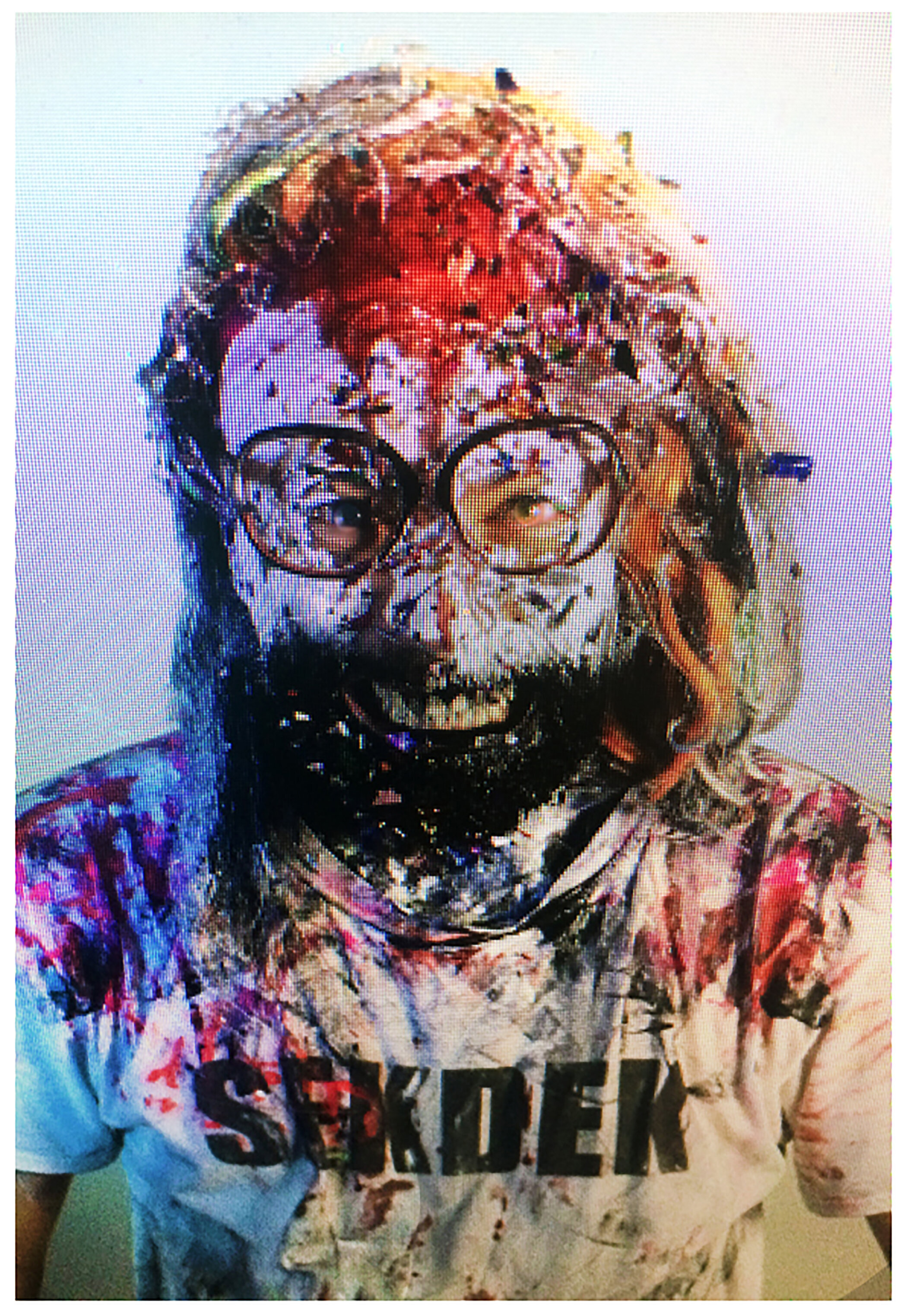

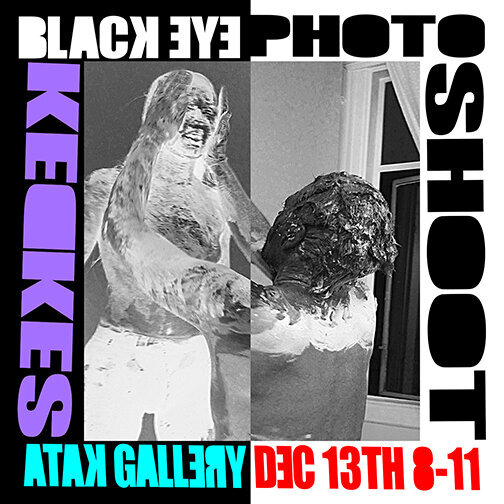

The painted torso art of Sekdek is also an undeniable representation of a vast and evolving body of work, meticulously developed over time. Each piece builds upon the last, creating a tapestry of themes, symbols, and transformations that reflect a relentless pursuit of deeper understanding and artistic refinement. It’s a living, breathing chronicle of growth and exploration, as much about the journey as the end result. Don't be scared. Open your eye wider than ever before and look deeply into your own soul. I am a mirror. I am a psychedelic. I am Sekdek! aka The Mirror.